Biak na Bato Weed Garden

2025

Dimensions Variable

Mountain Dew bottles, artificial pearls, local cement, locally foraged stones

One of the most recognizable reuses of bright green Mountain Dew bottles in the Philippines is turning them into decorative flowers—a practice that, for some, provides a livelihood. Inspired by this contemporary craft (and at times, a form of economic survival), this work repurposes Mountain Dew bottles collected from the local landscape, reshaping them into decorative weeds and placing them back into that same environment.

I installed them in places where the built and natural worlds collide—like sidewalks that encase immovable boulders instead of removing them. These moments reflect a relationship with land that sees the built world as inseparable from nature. At the same time, such improvised infrastructure reveals deeper issues: a chronic lack or misallocation of government funding that hinders the development of resilient systems meant to serve the public.

Expanding on my interest in wayfinding and the navigation of art’s political role, this piece takes form as a temporary sculpture garden dispersed across Lucban. These small, vivid interventions—scattered through both urban and rural spaces—create a kind of trail guide along one of my routine walks from Project Space Pilipinas to my site-specific installation on the town’s outskirts, Beneath (Lupa Sa Magsasaka).

Pasalubong #18

2025

~ 34" x 68"

Handwoven Mountain Dew bottles, grommets, plastic bag cordage

Beneath (Lupa sa Magsasaka)

2025

Dimensions Variable

Cast Paving Stones (Local Cement, Sand and Gravel, Paint, Mountain Dew Bottles), Decorative Weed (Mountain Dew Bottle, Artificial Pearls, Local Cement, Locally Foraged Stone)

Site: Lucban-Tayabas Road

Inspired by the slogan of the 1968 worker protests in France, "Beneath the paving stones, the beach," the use of paving stones in my practice has been a way for me to talk about political agency. Here, it became a marker for someone else's political agency in the form of graffiti that reads “Lupa sa Magsasaka” or “Land to the Farmer, “ bringing attention to the basic problem of landlessness in Philippine society, the phrase is a call for genuine agrarian reform. The work takes the form of a cairn, or a pile of stones intentionally arranged and left behind in the landscape as a way marker. Building off of previous works that used Mt. Pinatubo volcanic ash to create new landmasses of the Philippines in the form of paving stones abroad, this work also uses paving stones cast using local cement. However, in this piece, the stones have been created with a higher ratio of locally foraged sand, gravel and litter from the surrounding Mt. Banahaw, meaning that the stones will break down and become a part of the landscape again more rapidly. For me, this work is a way to ask questions about the role and limitations of art in political action, and to think about how we all must navigate these forking paths.

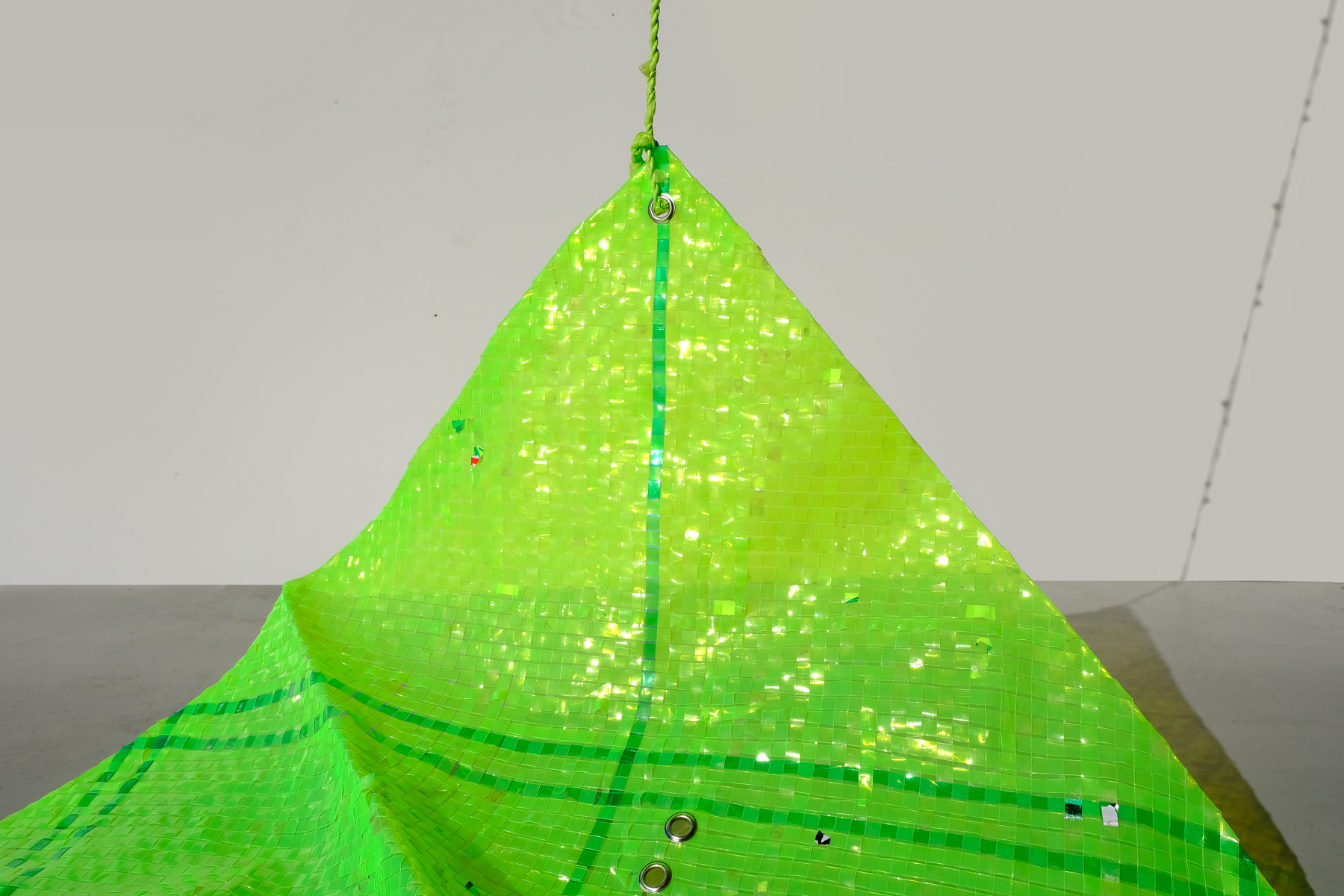

Pasalubong #19

2025

~ 32" x 64"

Handwoven Tarpaulin, Grommets, Plastic Bag Cordage

Pasalubong #19 (Bagyo) reflects on the double-edged persistence of traditional knowledge and craft in the face of ongoing instability—economic, environmental, and political. Made from blue and orange tarp—a material linked to displacement and temporary shelter—it’s woven in an oblique binakol, a pattern not normally applied to banig or palm weaving—its superstitious optical illusions evoking storms or whirlwinds once meant to ward off harm. This banig inspired work embodies the creative adaptation people are forced to take up to navigate the forces—natural and man-made—that shape life in the Philippines today.

The work gestures toward the increasing frequency of storms, typhoons and floods impacting local communities and the state’s continued failure to respond with foresight and preparation. Rather than invest in environmentally-realistic, people-centered disaster risk reduction, the government enables and profits off of ecologically destructive development: land reclamation, luxury resorts, coastal displacement. Those most affected by the aftermaths of development aggression are left to endure—often without support, and too often, being blamed for the conditions they have no choice but to endure.

Still, weaving continues. Across the islands, the craft of banig holds space for survival, memory, and care. When disaster halts daily life, weaving offers continuity—income, grounding, and solace. In times of crisis, banig are sent not just for rest, but as quiet gestures of connection. Throughout the diaspora, they endure as poignant symbols of home.

The work’s woven strips speak of entanglement—with each other, with land and sea, with histories we inherit, and futures we must be resolute to shape. At the heart of Pasalubong #19 (Bagyo) are simple but urgent questions: What does protection look like today? Why is the resilience of the Filipino people in the face of disaster glorified? Who in our society bears the brunt of climate crisis and for whom are governmental infrastructure projects actually initiated?

Walang Buwan III (The Drowned World)

2024

Featured in Festival for Philippine Arts and Culture’s inaugural ArtPhair

Mixed Media Installation (Blue tarp, plastic water bottles, dyed pandan, dichroic film, grommets, plastic bag cordage, stools, Pinatubo ash planters, pandan plant, salt)

"Walang Buwan III (The Drowned World)" is a large-scale installation that combines traditional Filipino weaving techniques with blue tarp. This site-sensitive work addresses the use of tarps as temporary fixes in the aftermath of climate disasters such as typhoons, floods, and landslides. The installation's oversized woven tarp creates a canopy, evoking the traditional banig used in the Philippines for gathering, ritual, and rest.

The title “Walang Buwan,” meaning “moonless” in Tagalog, refers to uncontrollable earth systems affected by human activities. The piece aims to raise awareness about the loss of traditional knowledge due to the economic instability and climate imperialism that plague the Philippines. It reflects on the frequent typhoons and massive flooding that devastate urban and rural areas alike, highlighting the government's failure to address these issues effectively.

Despite calls for people-centered disaster risk reduction plans, the Philippine government continues to prioritize environmentally destructive projects like land reclamation, militarization and luxury developments. This negligence exacerbates the impact on local communities, who are often blamed for the failures of state infrastructure and neglected in disaster aid distribution.

It critiques the normalization and glorification of Filipino resilience in the face of escalating natural disasters and underscores how intertwined we all are with our environment, and with one another—even if we are an ocean away.